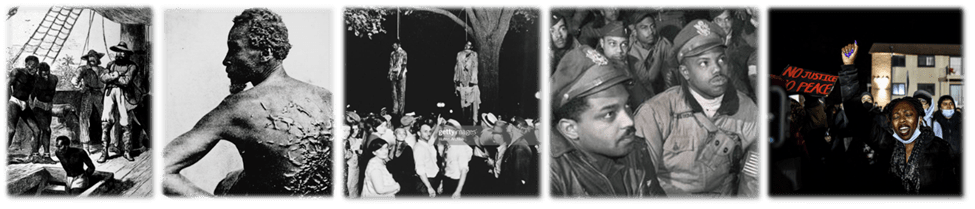

This paper examines cases of bias in AI and statistical models that affect our lives, and how we can better understand the causes of that bias and propose solutions that repair both the models and society itself.

AI and traditional statistical models are used to run search engines, dating applications, and streaming services. They are also increasingly used in hiring, college admissions, home loan applications, welfare distribution, health care provision, policing, and criminal sentencing.

We expect these algorithms to be fair. There is growing evidence that many are not.

Two examples:

- A facial recognition algorithm used by police departments in several countries falsely matched Black women’s faces ten times more often than white women’s faces, leading to more wrongful arrests of Black women.[1]

- A researcher tested Google News Feeds for gender bias using a technique that finds common associations in the data. Here are a couple examples of the associations he uncovered: man is to computer programmer as woman is to homemaker; father is to doctor as mother is to nurse.[2]

The fairness problem in the first example results from insufficient data and can be fixed by adding more pictures of Black women to the training dataset. The second example presents a more fundamental issue. There is bias in the Google News Feed data used to train the model, i.e., in the language used and news stories told that reflect traditional notions about the roles of women and men in society.

Three additional examples illustrate what happens when the data we use is biased:

- ProPublica journalists found that COMPAS, a model that forecasts whether an arrested person is likely to commit a crime if given parole, incorrectly predicted a higher recidivism rate for Blacks than for whites.[3]

- Amazon found that their model for discovering good job candidates for technology roles significantly favored men over women.[4]

- IBM found that white women were twice as likely as Black women to be diagnosed with postpartum depression despite no obvious physiological explanation for that difference.[5]

These examples have three characteristics in common.

- The models rely on a key variable that is a flawed proxy for what we really want to measure:

- Historical arrest rates are a bad proxy for crime rates if there is over policing in African American neighborhoods that drives higher arrest rates in those areas.

- A training set of previously successful Amazon job candidates is a bad proxy for future success because most of Amazon’s IT employees, and 68% of the IT industry, are men, and there are likely plenty of good female candidates.[6] In fact, Amazon found that “any indicator of feminine gender identity in an application lowered the applicant’s score … a degree from a women’s college, participation in women-focused organizations, and feminized language patterns all reduced the evaluative outcome.”[7]

- The fact that Black women have not received as much care for postpartum depression as white women is a bad predictor of whether they would benefit from that care if it were available.

- We can sense that there are underlying societal issues causing the fairness problem in these models, namely a history of structural bias in policing, the technology industry, and health care.

- These algorithms create a self-fulfilling prophesy, perpetuating and exacerbating bias:

- Over policing increases arrest rates in Black neighborhoods causing the model to send more police to those neighborhoods, which in turn causes more arrests.

- Amazon’s model favors men, so more men are hired, and the model learns it was right to rank male candidates higher than females.

- Because African American women receive less health services, the model believes they don’t need those services, so fewer services are predicted and provided.

How can we test if models are fair and fix them if they are not?

Fairness can be measured at the group level (are women and men treated fairly?) and at the individual level (are two people from different groups treated the same, all other things being equal?). Within these categories, writers have proposed various technical definitions of “fair” and “the same,” e.g.:

- Anti-classification or fairness through blindness: A model is fair if information about a sensitive attribute (e.g., gender, race, or sexual orientation) is masked or taken out of the dataset so it can’t affect the results. From a race perspective, the model is “color blind.”

- Demographic parity: A model is fair if it selects members of protected groups at the same rate, e.g., a university’s AI model selects 10% of the Black applicants and 10% of the white applicants.

- Equalized odds: A model is fair if members of different groups exhibit the same error rates. For example, a police force’s facial recognition software incorrectly identifies 1% of white women and 1% of Black women.

These three definitions often conflict with each other. Using Amazon’s hiring algorithm:

- If Amazon masks gender, they certainly will not achieve equal selection of women and men because their dataset is dominated by men.[8]

- If they force the model to select women and men equally, they are no longer gender-blind, and they will likely fail the equalized odds test because of higher error rates for women.

So, which definition of fairness do we use? And, when the definition shows our model is not fair, how do we fix it?

Several methods have been developed to detect and mitigate bias in models and the training datasets they use. IBM, a leader in Fair AI, has developed an open-source software toolkit containing the most common of these techniques.[9] These methods often use constraints, or trade-offs, between utility and parity. In other words, we ask the model to solve for the optimal outcome – the best job candidate or university applicant – given, or constrained by, a desired level of gender or racial diversity.

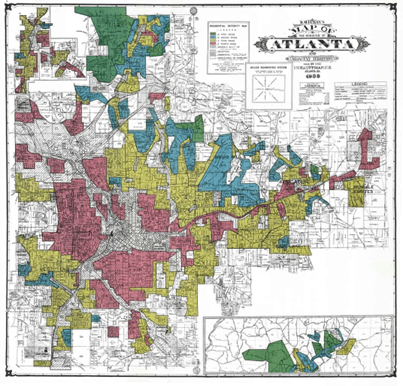

Let’s take the example of mortgage loans. For many years, banks avoided lending in Black neighborhoods, a discriminatory practice known as redlining that was condoned and supported by the Federal Housing Administration and the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation.[10] Because homes are Americans’ most valuable assets,[11] the resulting lower homeownership rate for Black families has been and remains a major contributor to a 10:1 wealth gap between white and Black families in the US.[12]

Banks decide whether to lend money for a mortgage based on the creditworthiness of the applicant and other factors, most of which are related to wealth and income. Black applicants are denied a mortgage 84% more often than whites because, as with the three models discussed above, the banks’ algorithms embed and reinforce bias in lending.[13]Discrimination against Blacks leads to less homeownership, which leads to less wealth, which leads the bank’s algorithms to reject African Americans because of insufficient wealth, which makes it difficult without homeownership to amass wealth, and on and on, a phenomenon the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the Civil Rights Division of the US Department of Justice, is still fighting today.[14]

How do we break this cycle? What would be a “fair” algorithm for approving mortgages given the history and persistence of lending discrimination? Should the banks’ models force higher approval rates for Black families than white families at similar wealth and income levels? If so, how should the banks set that threshold? There is nothing in the algorithms per se that tells the bank that they should approve, for example, 20% more loans for Black families than an unconstrained model would approve.

In employment cases, not bank loans, the EEOC has suggested a rule of thumb of four-fifths,[15] meaning that the percent of minority job applicants or promotion candidates selected should be no less than 80% of the percent of whites selected. But this is an arbitrary number, and employment practices are different than bank loans. And anyway, is it the bank’s job to fix societal discrimination?

There is a relatively new line of research on fair algorithms that may help us avoid arbitrary fixes, and also help answer the question of who should pay to repair bias when we find it. In a word, causation.

Remember that sense we had that something else was operating in the background of the unfair models, those underlying structural problems with policing, the IT industry, and health care that seemed to be causing the persistent bias we detected? How can we mitigate that bias if we don’t understand and measure those causes?

In Causal Reasoning for Algorithmic Fairness, Loftus, et al. state:

This approach [causal models] provides tools for making the assumptions that underlie intuitive notions of fairness explicit. This is important, since notions of fairness that are discordant with the actual causal relationships in the data can lead to misleading and undesirable outcomes. Only by understanding and accurately modelling the mechanisms that propagate unfairness through society can we make informed decisions as to what should be done.[16]

How would this work in practice? A group of researchers from MIT, IBM and Microsoft provide us with an example using the mortgage discrimination problem. They develop two case studies:

The first case study shows how institutionalized redlining, which denied mortgage insurance to neighborhoods that Black people and immigrants most lived in from the 1940s to 1960s, affected the accumulation of wealth through housing.

Then, the second case study develops an ML [machine learning] system that shows the estimated cost of reparations if we wish to intervene in today’s mortgage lending to address historical harms.[17]

In other words, the first algorithm models the causes of discrimination in lending; the second tells us how much it would take to repair those wrongs. The answer: to change 39,000 rejections of bank prime loans to accept would require average support to Black applicants of $41,256 for the downpayment and $205/month for the mortgage. For an FHA loan, no downpayment support is required and the average monthly subsidy would be $578. These results are specific and transparent, based on models that can be demonstrated and reproduced, not arbitrary criteria like the 4/5th rule. The result can be readily compared, for example, to the housing grants of $25,000 the city of Evanston provides as reparations to the descendants of slavery.[18]

Now, admittedly, housing discrimination lends itself to causal analysis. There is a lot of data, the history has been thoroughly studied, and the causal links are strong and self-perpetuating. Perhaps other forms of racial, gender or sexual-orientation discrimination would be tougher to model. Or perhaps we are simply waiting for the right people to take on the challenge!

Who are the right people? Unlike the previous bias mitigation techniques, causal models require domain knowledge to posit and test how and why bias occurs, not simply observe it. That means data scientists building AI algorithms must work with experts from civil society and universities.

We should also add lawyers. Could the affirmative actions proposed by these causal models survive court scrutiny, even the current Supreme Court?

What about SCOTUS?

US civil rights law generally defines two types of discrimination: disparate treatment and disparate impact. For our purposes, disparate treatment would be intentionally creating models that discriminate against protected groups, and then acting on the results. Disparate impacts are unintended outcomes that are discriminatory.

In our cases, these two concepts are often in conflict. We are purposely creating models that treat two protected classes differently (disparate intent) to reduce disparate impacts. Is that legal?

In two decisions, Steelworkers v. Weber and Johnson v. Transportation Agency,[19] the Supreme Court defined criteria employers could use to purposely favor minorities or other protected groups, i.e., use affirmative action to address historical discrimination:

- Employers must be responding to a “manifest imbalance” in “traditionally segregated job categories”, i.e., reacting to a clear case of historical discrimination.

- They must have an affirmative action plan in place before they act.

- That plan should not “unnecessarily trammel” the rights of others.

- The actions should be temporary.

The mortgage loan example satisfies these criteria:

- The causal models clearly demonstrate, and quantify, manifest imbalances.

- Any reparative action to affect the racial wealth gap would likely require a law like the one Evanston passed, and the ones Congress, California, New York, and a dozen cities are considering. These would be affirmative action plans embedded in the law.

- If the government provides direct subsidies to Black families, the models would not change the outcomes for other races, just for African Americans.

- Any reparative actions would be temporary (perhaps a couple generations), until the harm is mitigated.

But these two cases are over 30 years old, and the current Supreme Court is much more skeptical about affirmative action programs. In its recent decision outlawing affirmative action in university admissions, the Supreme Court went further, emphasizing three additional problems with the affirmative action programs at Harvard and University of North Carolina:

- “The interests that respondents view as compelling cannot be subjected to meaningful judicial review.”

- “Respondents’ admissions programs fail to articulate a meaningful connection between the means they employ and the goals they pursue.”

- “They require stereotyping … When a university admits students on the basis of race, it engages in the offensive and demeaning assumption that [students] of a particular race, because of their race, think alike.”[20]

The first two points are precisely the reason for causal algorithms: so that the interests of society can be studied and mapped, and so that the connection between the means and the ends can be defined and quantified. The third point does not apply to our mortgage loan example. No one is saying Black families all think alike. Just that they have been discriminated against in homeownership.

So, in summary, even in the current environment, these explicit causal models may provide a defense against judicial scrutiny.

What if…

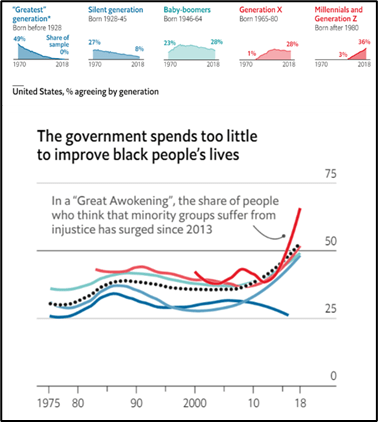

AI is all the buzz these days. Everyone is writing machine-learning algorithms to do everything. AI will apparently save the stock market, and even the economy.[21] Governments are trying to legislate.[22] The public is concerned.[23]

We have seen how these models make decisions that can affect some of the most important aspects of our lives – getting a job, a mortgage, or a spot at a good university – and how they often embed and reinforce the biases present in society.

What if the IT industry, universities, and nonprofits devoted a portion of their resources, say one-half of one percent, to developing models that detect and repair bias, and shared their results with the public? How would that information change perceptions, practices, and policy? Could knowing more about the causes of discrimination and how to fix them help us reduce the STEM gap,[24] the Black wealth gap, or the political chasm that divides Americans? It’s worth a try.

[1] The best algorithms struggle to recognize black faces equally.

[2] Man is to computer programmer as woman is to homemaker?

[3] How we analyzed the COMPAS recidivism algorithm.

[4] Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women.

[5] IBM researchers investigate ways to help reduce bias in healthcare AI.

[6] Women in tech statistics highlights.

[8] In fact, “color blind” anticlassification has been shown time and again to be nothing of the sort. People who want to discriminate simply find a strong proxy for race, e.g., ZIP codes in highly segregated cities.

[9] IBM’s AI Fairness 360 toolkit.

[10] See The Federal Reserve’s History of Redlining for the Federal Reserve’s brief history of redlining.

[11] Cleveland Fed’s Evaluating Homeownership as the Solution to Wealth Inequality.

[12]In 2017, mean white family wealth in the US was 10 times higher than mean Black family wealth. See How wealth inequality has changed in the U.S. since the Great Recession, by race, ethnicity and income.

[13] Black mortgage applicants are denied 84% more often than whites.

[14] See Justice Department Announces New Initiative to Combat Redlining for a description of a Department of Justice Civil Rights Division anti-redlining initiative launched in 2021.

[15] Questions and Answers to Clarify and Provide a Common Interpretation of the Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures.

[16] Causal Reasoning for Algorithmic Fairness.

[17] Beyond Fairness: Reparative Algorithms to Address Historical Injustices of Housing Discrimination in the US.

[18] City of Evanston Reparations.

[19] US Supreme Court Steelworkers v. Weber and US Supreme Court Johnson v. Transportation Agency.

[20] US Supreme Court Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College.

[21] CNBC The AI explosion could save the market and maybe the economy.

[22] Harvard Business Review Who is going to regulate AI?

[23] Pew Research Awareness of artificial intelligence in everyday activities.

[24] The STEM Gap: Women and Girls in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics.