Frederick Douglas, Republican National Convention, 1876

When the Russian serfs had their chains broken and were given their liberty, the government of Russia—aye, the despotic government of Russia—gave to those poor emancipated serfs a few acres of land on which they could live and earn their bread. But when you turned us loose, you gave us no acres: you turned us loose to the sky, to the storm, to the whirlwind, and, worst of all, you turned us loose to the wrath of our infuriated masters.

The Oxford dictionary defines reparations as “the making of amends for a wrong one has done, by paying money to or otherwise helping those who have been wronged.” Courts routinely assess monetary awards for damages suffered. Indigenous people in the US and Canada, Japanese-Americans interned during WWII, and holocaust survivors of Nazi concentration camps have received reparations. In the last of these examples, German restitution not only helped build the state of Israel but served as one element of a process of education and healing that is visible today: according to the Anti-Defamation League, 15% of Germans hold anti-Semitic views vs. 30% in Europe as a whole.[1] As Israel’s first Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion, said:

For the first time in the history of relations between people, a precedent has been created by which a great State, as a result of moral pressure alone, takes it upon itself to pay compensation to the victims of the government that preceded it. For the first time in the history of a people that has been persecuted, oppressed, plundered and despoiled for hundreds of years in the countries of Europe, a persecutor and despoiler has been obliged to return part of his spoils and has even undertaken to make collective reparation as partial compensation for material losses.[2]

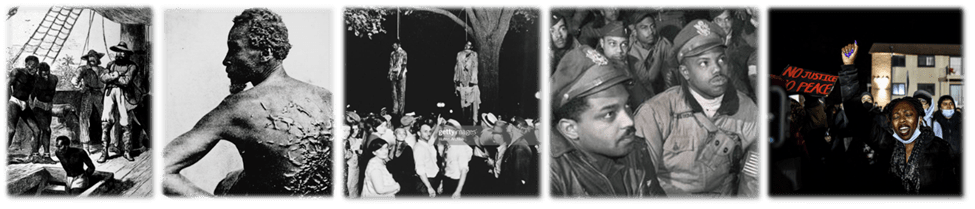

The case for reparations for African Americans is clear and compelling. Africans were brought in chains to the New World; held in bondage for 250 years; subjected to the Jim Crow racial caste system in the South for another 100 years, and continue to face a legacy of housing, education, employment and criminal justice discrimination to this day. Some examples:

- At southern Senators’ insistence, Social Security, America’s single most important benefits program, excluded farm workers and domestics, making 75% of Black workers in the South and 60% of all Black workers in the US ineligible.

- The GI Bill provided subsidized loans for 30% of all homes purchased in the 10 years after WWII and higher education for half of WWII veterans. Local implementation of the GI Bill meant that, in Southern States like Mississippi where in 1947 only two of 3,229 GI Bill home loan recipients were African American, Kathleen J. Frydl writes that “it is more accurate to say that blacks could not use this particular title.”[3] The North was not much better. In the same period, only 100 of 67,000 GI Bill-backed mortgages in New York and New Jersey went to non-Whites.[4] Black veterans also found it nearly impossible to attend white universities: 95% of the few African American vets who secured GI Bill loans attended overcrowded, underfunded, and segregated Black universities.[5]

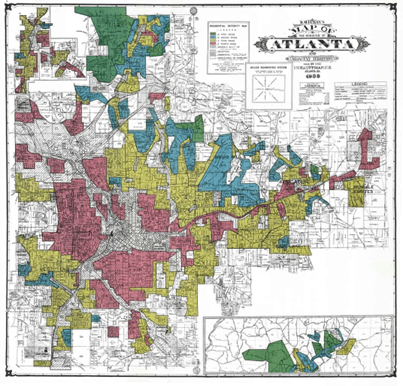

- Redlining, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation and Federal Housing Administration practice of denying government-backed housing loans in minority neighborhoods, was outlawed over 50 years ago but its impact lives on. A recent study found that 64% of neighborhoods redlined 80 years ago remain minority neighborhoods today and 74% remain poor.[6]

Thus, the two most important drivers of wealth – education and home ownership – and the most important benefits program in US history – social security – were routinely denied to African Americans.

The legacy of these and other injustices can be seen in many economic and social indicators today, including incarceration rates (5X higher for Blacks than Whites), unemployment (2X higher for Blacks), and family income (35% lower for Blacks). Of these indicators, the clearest sign of the lasting legacy of slavery, segregation and racism is the African American family’s lack of wealth:

- The median Black family in America has only one-tenth the wealth of their White counterpart ($17,000 vs. $171,100).[7]

- Only 42% of African American families own their homes compared to 73% of Whites. In fact, Black college graduates are less likely to own a home than White high school dropouts.[8]

Today, 60 years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, Black families struggle to accumulate enough wealth to pass it down to the next generation: to bequeath a home to a daughter or pay for a grandson’s college education.

As William Darity Jr. and A Kirsten Mullen find[9], this inability to accumulate wealth is not the result of bad behavior. None of the oft cited “causes” of Black poverty can explain the wealth gap:

- Single parent families: single white parents have more than 2X the wealth of married black parents.

- Profligacy: At similar income levels, Blacks’ savings rates are the same as Whites’.

- Educational attainment: At similar income levels, Blacks obtain more years of schooling than Whites. But single Black household heads with a university degree have less net worth than Whites who never finished high school, and Black women with a college degree have a median net worth of $11,000 vs. $384,000 for their White counterparts.

And it is not getting any better. Over the last 55 years:

- Black homeownership has only increased 1%

- Black household income has remained between 55% and 60% of White household income.

One hundred and fifty years after the end of slavery, the wealth gap is still 10 to 1. Neither legislation, nor affirmative action, nor protest has made a difference. Shall we wait another 150 years to see if anything changes, or should we repair this wrong?

How much?

A number of methods have been proposed to calculate the size of reparations for descendants of slavery. These include estimating the present value of:

- The income slaves would have earned if they had been free

- The wealth their labor created

- The land they were promised but never received

- The income Blacks would have earned after slavery had there been no discrimination

These estimates generally range from hundreds of billions to tens of trillions of dollars.

A metric that is arguably the best representation of the impact of years of oppression and discrimination on Black families is the wealth gap between White and Black families.[10] The difference between mean family wealth – $934,000 for Whites and $138,000 for Blacks – times the number of Black households yields $13 trillion, or $318,000 for each African American.

This might sound like an impossibly large number, but in fact it is roughly equal to the cost of the COVID stimulus packages plus President Biden’s three big spending bills. Paid out over 20 years, the annual amount, $650 billion, would equal only 10% of the federal budget and be roughly the size of the annual American subsidy to the fossil fuel industry.[11]

This amount could be funded by the Federal Reserve (between March 2020 and March 2023 the Fed created $5 trillion through quantitative easing), by running a deficit (the 2022 federal deficit was $1.4 trillion) or by increasing taxes (a 13% increase would be required). The first two methods would be inflationary, but only to the extent that these payments fail to create new value in the economy.

For whom? How?

The California reparations commission recommends compensation to African Americans who can identify a Black descendant living in the US prior to 1900. We should also consider people who cannot track their ancestry back that far given the damage done to Black families by continued discrimination in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Experts argue for a variety of compensation methods including direct payments and grants for homeownership, education and entrepreneurship. Payments could be spread out over time. In The Case for Black Reparations Boris Bittker proposes 20 years.[12] Such a long period gives time for intergenerational dynamics and for the agencies managing the program to try different models. As with any big program, e.g., the New Deal or the War on Poverty, experimentation is key, adjusting as information on outcomes becomes available. The program must also include significant funds for communications, outreach, atonement, and education. As with the case of Germany discussed above, successful reparations efforts must improve society, not just compensate for past wrongs.

The history of reparations in the United States

Individual freed slaves have demanded, and in a few cases won, compensation for their enslavement starting as early as 1783. The most famous attempt to compensate ex-slaves was General William Sherman’s land grant of 40 acres (and a surplus government mule when available) to freed slave families. After Lincoln’s assassination, however, President Andrew Johnson quickly rescinded that order stating, “This is a country for white men and, by God, as long as I am President, it shall be a government for white men.” After the failure of Reconstruction, the question of reparations was rarely raised until the Civil Rights era, and then with little success.

Then, beginning in the late 1980s, legislatures, courts and commissions began exploring massacres of Blacks in Rosewood Florida (1923), Tulsa Oklahoma (1921) and Wilmington North Carolina (1898). Law suits were brought against the US Department of Agriculture and Prince Edward County, Virginia (the latter because the County shut down its public schools for 5 years beginning in 1959 to avoid desegregation, providing vouchers to White children). All of these cases were successful in that they concluded that genuine, egregious harm had been done, but very little money changed hands.

Why now?

Legislatures are beginning to act

Beginning in 1989 and every year after that for 28 years, Representative John Conyers introduced a bill in the US House of Representatives, HR 40 (for “40 acres and a mule”), to create a commission to study the question of reparations for the ancestors of slaves. Finally, in 2021, it was successfully voted out of the House Judiciary Committee. With over 200 cosponsors, it has a real chance of passing if Democrats take back the House in 2024. As always on civil rights issues, the Senate is a tougher challenge but, if the House passes HR 40, the 40 Senators currently supporting a similar bill might be able to pass it if they time debate to coincide with the next inevitable spate of police shootings, particularly since the bill only studies the question of reparations.

Thirteen cities have commissions studying reparations. One, Evanston Illinois, has begun compensating African Americans. In June, New York passed a bill to create its commission and the California commission issued its recommendations. The California report concluded that reparations are required, proposed mechanisms for calculating compensation, and described programs that should be implemented. The state legislature will likely take up the report in the Fall.

Perceptions are beginning to change

Black Lives Matter, the New York Times 1619 Project, reparations commissions, press reports, campus debate: people are talking about race in America. And, despite White backlash since 2020 and the Supreme Court’s actions against affirmative action, there are signs that old perceptions are changing. According to Pew Research, between 2002 and 2021, the percent of Americans that support payments to the descendants of slaves more than doubled from 14% to 30%.[13] While certainly not a majority, this is progress nonetheless.

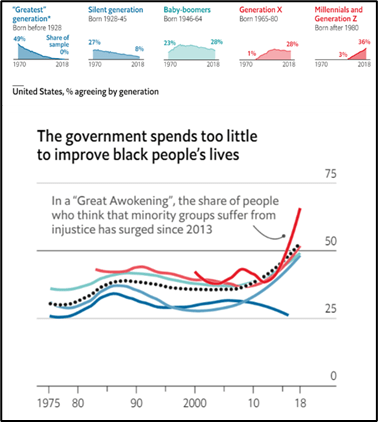

In 2019, the Economist published a set of charts under the title, “Societies change their minds faster than people do.” The charts made three points:

- Demographic shifts are often more important than changes in individuals’ views, as shown by the declining impact of the “Greatest generation” in the chart below.

- This can result in rapid changes in societal perceptions, e.g., a 45-point increase in support for same-sex marriage within 18 years.

- Like support for gay marriage, support for more government spending to improve Black lives “has surged.” (See the chart to the right).

What would it take to build on that surge to create a consensus? A national dialogue, which is exactly what would happen if Congress passed HR 40. Passage of this bill is a critical first step.

This paper opened with a quote from Frederick Douglas in 1865. In response to those who believe a focus on Black reparations is inappropriate because it ignores poor Whites, the paper closes with a quote from Lyndon Johnson nearly 100 years later:

Negro poverty is not white poverty. Many of its causes and many of its cures are the same. But there are differences – deep, corrosive, obstinate differences – radiating painful roots into the community and into the family, and the nature of the individual. These differences are not racial differences. They are solely and simply the consequence of ancient brutality, past injustice, and present prejudice.[14]

We can repair Black families and, in so doing, repair America.

[1] How Germany paid reparations for the Holocaust (qz.com).

[2] https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

[3] Frydl, Kathleen, The GI Bill, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

[4] https://www.bostonglobe.com/2022/02/23/opinion/gi-bill-was-one-worst-racial-injustices-20th-century-congress-can-fix-it/.

[5] Brown, Nikki L.M. and Barry M. Stentiford, The Jim Crow Encyclopedia, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008.

[7] https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2017/11/01/how-wealth-inequality-has-changed-in-the-u-s-since-the-great-recession-by-race-ethnicity-and-income/.

[8] https://www.urban.org/events/black-homeownership-gap-research-trends-and-why-growing-gap-matters.

[9] Darity, William and A Kirsten Mullen, From Here to Equality: Reparations for African Americans in the Twenty-first Century, University of North Carolina Press, 2020.

[10] The mean is more appropriate than the median because it reflects the total value earned by all Whites and Blacks, including the very wealthy.

[11] Still Not Getting Energy Prices Right: A Global and Country Update of Fossil Fuel Subsidies (imf.org).

[12] Bittker, Boris, The Case for Black Reparations, Beacon Press, 1972.

[13] https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/11/28/black-and-white-americans-are-far-apart-in-their-views-of-reparations-for-slavery/.

[14] https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/commencement-address-howard-university-fulfill-these-rights.